RL - 52 years later, the Richard Riot is still brought up and discussed. Below, Buffalo sports writer and NFL expert Larry Felsner (Pro Football Hall Of Fame writer) tackles the fateful day in Habs lore and gets it half right. You can tell his colors right off from the opening sentence - he ain't too well versed in hockey history to be touching on most of this. Still the story is always a compassionate read, despite the inconsistancies with truth and myth. I've tried to clear up most of Felsner's boob's with comments in brackets. Beyond Felsner's account, there is a second one sprinkled with videos of the events and pictures added. Enjoy!

From Larry Felsner,

HOF Magazine:

Hockey has always been a niche sport, considered a superb game by those of us who love it, but largely ignored by hordes of other sports fans who reside south of the Canadian border.

The niche has never been smaller than the ‘50s, when the National Hockey League consisted of a mere six teams – the Chicago Black Hawks, New York Rangers, Detroit Red Wings and Boston Bruins in the U.S. plus the Montreal Canadiens and Toronto Maple Leads in Canada. Occasionally a few of the American owners might urge that the league be expanded, but most of the moguls were satisfied with what they considered a cozy setup. (RL - The expansion of 1967 was pioneered and executed mostly by Hab's GM Sam Pollock's insistance.)

Their feeder system, which supplied all but a tiny percentage of talent ( RL - It supplied all of it! ) to the NHL six, consisted of junior teams spread coast to coast across Canada, all of which were controlled – and sometimes wholly owned – by the major league clubs. The major league's control often reached down into the pee-wee leagues, so if a talented young player began serious competitive play for an affiliate of the Bruins, Maple Leafs or one of the others, he would remain the property ( RL - C-Form deafting.) of that organization until they traded or released him. With so much talent stockpiled in so few farm systems, the pay scales could be easily controlled, too.

It wasn't quite cradle-to-grave ownership, but it was close. Nowhere was the stamp of the parent team more traditional than in the Province of Quebec, where boys of French-Canadian heritage yearned to be happy serfs of the Canadiens.

By 1955 (RL - Try 1930!), the Montreal team, referred to as "the Flying Frenchmen" in newspaper sports sections all over North America, was established as the model of the NHL system. Montreal had a few outstanding Anglo players such as Doug Harvey, the all-star defenseman, and Dickie Moore, the reliable winger. But the core of the team was Gallic: Bernie "Boom-Boom" Geoffrion, the first to perfect the slap shot; Jacques Plante, the first goalkeeper to wear a mask; the regal center-man, Jean Belliveau; prize rookie Henri Richard and, most prominently, right wing Maurice Richard, the face and symbol not only of a hockey team, but of an entire province, Le Belle Quebec, in all its pride.

Eventually Maurice Richard was christened "the Rocket," (and later his kid brother Henri "the Pocket Rocket") yet the elder Richard did not barge into the NHL in the manner of Wayne Gretzky, and more recently, Sidney Crosby. As a junior he was considered injury prone (RL - Rocket was considered a top rank prospect, then suffered two key injuries.), and when he finally reported to the Canadiens as a rookie, he was rehabilitating from a broken leg. At first management feared that he would never be fast enough to fly with the other French stars, and the Montreal front office considered releasing him.

Instead, they gave him a second chance (RL - I'd suggest he earned it with 11 points in 16 games!), placing him on a line with two experienced veterans, left wing Hector "Toe" Blake and center Elmer Lach. The youngster, who had been the last man to make his junior team, flourished. The media nicknamed the trio "the Lamplighter Line," for the frequency for which the right goal light flashed for them. When Richard scored an unprecedented 50 goals in 50 games during the 1945-46 (RL - 2 seasons later.) season, the name "Rocket" was attached to him forever.

The names his opponents called him were far less printable. His will to win knew few bounds, literally.

There is a life-size sculpture of Richard in full skate outside a museum in Montreal's Olympic Park, but no sculptor, no matter how skilled, could capture his physical hallmark, his eyes. As Belliveau used to say, "He prefers to express himself on the ice. I would tell our younger players to watch the fire emanating from his eyes."

An opponent's view of Richard's relentlessness could be harrowing. "When he came flying toward you, "said Hall of Fame goalie Glenn Hall, "his eyes were all lit up, flashing and gleaming like a pinball machine." Wally Stanowski, a former Toronto player, went further. "He had that fiery look all the time," said Stanowski, "I once heard it described as having the look of an escaped mental patient. I thought that was a good description."

Late in his career, the Rocket suffered an Achilles tendon injury which kept him inactive for a long time, and there was some fear that his career might be ended. When he came back to play it was in the lair of Montreal's arch-enemy, Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. Richard didn't start the game, but played with the second line. When he jumped over the boards to come on the ice for the first time, there was a puck loose near the Leafs' blue line. He pounced upon it, like a lion on a young zebra. He launched his shot immediately, and it flew past Johnny Bower, another Hall of Fame goalie.

The Toronto fans, most of whom hated him, exploded in a rueful salute.

In a game on March 15 against New York (Boston) near the end of the 1955 season, Richard's competitive fury, which he managed to channel most of the time, became completely un-channeled. It started when the high stick of Ranger (Bruins) defenseman Hal Laycoe cut him and it drew blood. Laycoe was a former teammate of the Rocket's, but that didn't stop Richard from attacking him in revenge, hitting him across the shoulders and face with his stick. (RL - Richard also used his fists, after an initial stick blow.)

Finally, as the fight seemed to subside, lineman Cliff Thompson moved in to separate the combatants and return order to the game, which is part of a linesman's job. Richard did not wish to be soothed, and when Thompson tried to move him away from Laycoe, he punched the linesman twice in the face, knocking him unconscious. (RL - Actually Thompson approached and withheld Richard from behind as Laycoe decked him! Just a small, minute detail.)

As soon as the game ended, the referee filed a report to the NHL commissioner, Clarence Campbell, since attacking an official in hockey is just as serious as it is in any other sport. After digesting the report and pondering his options (RL - Apparently discussing it with the owners of the 5 other NHL teams! ) for two days, Campbell issued his decision: Richard would be suspended, not just for the last three games of the regular season, but for the entire Stanley Cup playoffs.

The people of the city of Montreal and the province of Quebec itself were thunderstruck. The Canadiens and Detroit were tied for first place in the league and were to meet that night in the Montreal Forum. The fan reaction was so immediate and furious in the city that the police commissioner warned Campbell, whose office and that of the league were located in Montreal, that it would be inadvisable for him to attend the game as was his usual custom. Public attitudes were so poisonous that his staff begged him not to even think about entering the Forum.

Hours before the opening face-off, crowds, most of whom did not have tickets, gathered on St. Catharines St. and adjoining streets around the Forum, and they were in a surly mood. At the Montreal Gazette, the editor, sensing that the usual number of reporters staffing a Canadiens game would not be sufficient to cover what might happen, assigned a young sports writer named Red Fisher (Fisher worked for the Montreal Star in 1955, not the Gazette.) to rush to the Forum, not to cover any aspect of the game, but to handle whatever other newsworthy event might occur.

Fisher, who was to become a journalistic legend in Montreal, had never before covered anything at the Forum, but as soon as he arrived he sensed that what was growing among the crowds, both inside and outside the building, was a possible riot. He was correct.

This was 12 years before Gen. Charles DeGaulle, the greatest Frenchman of the 20th Century, visited French Canada and finished his emotional speech with the words "Long Live Free Quebec!" Among those listening intently to DeGaulle was Rene Levesque, who would found the Quebec Separatist Movement that same year.

But the bitter feeling between Anglo Canada and Gallic Canada had been simmering for years, and it seemed to begin to boil over as a result of Campbell's suspension of Maurice Richard. After all, Rocket was a man of the Montreal streets who had grown up across the street from a prison. Early in his career, he spent a day moving his family out of their old house and into a new one, carrying heavy furniture up and down stairs. Then he went to work at the Forum, scored two goals and assisted on another (RL - Point of fact, it was a mere 5 goals and 3 assists in a crushing 9-1 win over Detroit!) in a Canadiens' victory. The people of Quebec saw themselves in him, and what they saw as an insult to him was also an insult to them and French Canada.

Clarence Campbell was a tall, dignified and austere man, a lawyer who had been a judge for Canada in the Nazi war criminal trials in Germany after World War II. He brushed aside warnings about showing up at the Forum, walking quickly to his seats, which were in the stands amid ordinary fans. With him was his secretary who later would become his wife. Their appearance amounted to a red flag in the face of bulls.

Red Fisher stationed himself on the stairway just below where Campbell sat. "People began throwing things at him – tomatoes, eggs, garbage – and one man walked right up to him and smashed a tomato right into Campbell's shirt. Then a guy whom I recognized as a local street thug walked up the stairs to Campbell's seat with a smile on his face, stuck out his hand and when Campbell reached to take it this guy punched him.

"There was a Detroit player, whom the Red Wings had made a healthy scratch for the game, who was in a seat near Campbell's. He came over and pulled the thug away and they began fighting."

Amazingly, the game began to go on. Midway in the first period, Detroit had the lead and the fans began to pelt Campbell with more vegetables and garbage. It was announced that Detroit was awarded a forfeit victory. Finally, a tear gas canister was detonated, and the Forum was evacuated. (RL - Tear gas first, forfeit afterwards.)

As the fans emptied the building and filled the streets, the riot began in earnest, with cars overturned, stores looted and fires started. The authorities reached Richard, who seemed stunned at the angry outpouring of the fans over his suspension and the riot that ensued. They asked him to help calm the city and he did. "I had to go on the radio and ask all the people who were doing damage on the street and to the stores to stop."

The rioting finally stopped the next day, but the fury of the people was slower to subside. Geoffrion, who was in a close race with Richard for the NHL scoring title, won it with the Rocket suspended in the final two games. "Boom-Boom" received death threats as a result.

Without Maurice Richard, the Detroit Red Wings won the Stanley Cup as well as the regular-season championship, but Richard would come back for five more seasons, all of which ended with the Canadiens winning the Cup. He retired in 1960.

Upon his retirement, some of the notable players against whom he competed were contacted for their reaction. Gordie Howe, Detroit's great right wing and Richard's fiercest rival, put his feelings succinctly: "He was a bastard."

At the closing of the Montreal Forum in 1996, a tearful "Rocket" received the longest standing ovation in the city's history. For some 16 minutes, adulation poured over him, the fans chanting his name over and over again. The "Rocket" died in 2000 and received a formal state funeral that was broadcast live across Canada.

Here, for perspective's sake, is a more accurate accounting of the event of the Richard Riot and suspension.

As Montreal's great star, it was common for Richard to be antagonized on the ice. Teams would reportedly send one or two players to do nothing more than annoy him, and throughout his career Richard was fined and suspended several times for retaliation assaults on players (and even officials). One such incident would spark one of the worst hockey-related incidents in history.

On March 13, 1955, Richard was given a match penalty for intentionally injuring Hal Laycoe, after he had been deliberatally struck in the head with a hockey stick by the player, in a game against the Boston Bruins.

Laycoe had highsticked Richard in the head during a Montreal power play. The referee signalled for a penalty to be called, but play was allowed to continue because the Canadiens had possession of the puck. Richard indicated to the referee that he'd been injured, and then skated up to Laycoe -- who had dropped his stick and gloves preparatory to a fight -- and struck Laycoe in the face and shoulders with his stick.

The linesmen attempted to restrain Richard, who repeatedly broke away from them to attack Laycoe, even breaking his stick over his back. Moments passed and a second linesman Cliff Thompson, restrained Richard by holding both his arms in a lock. Richard broke loose and punched Thomson twice in the face, knocking him unconscious. Richard later said at a league hearing that he thought Thompson was one of Boston's players.

Given that it was Richard's second assault on an official in that season alone, a formal inquiry took place on March 16 after which NHL president Clarence Campbell made the following statement:

"I have no hesitation in coming to the conclusion that the attack on Laycoe was not only deliberate but persisted in the face of all authority and that the referee acted with proper judgment in accordance with the rules in awarding a match penalty. I am also satisfied that Richard did not strike linesman Thompson as a result of a mistake or accident as suggested. There is singularly little conflict in the evidence as to important relevant facts. Assistance can also be obtained from an incident that occurred less than three months ago in which the pattern of conduct of Richard was almost identical, including his constant resort to the recovery of his stick to pursue his opponent, as well as flouting the authority of and striking officials. On the previous occasion he was fortunate that teammates and officials were more effective in preventing him from doing injury to anyone and the penalty was more lenient in consequence. At the time he was warned there must be no further incident. It was too bad that his teammates did not assist officials instead of interfering with them. The time for probationary lenience has passed, whether this type of conduct is the product of temperamental instability or willful defiance of the authority of the game does not matter. Richard will be suspended from all games both league and playoff for the balance of the current season."

The suspension - at the time, the longest in NHL history for an on-ice incident - was considered by many in Montreal to be unjust and severe. Detroit Red Wings General Manager Jack Adams leapt to Campbell's defence, saying that Richard was becoming "too big for the league" and needed to be "put in his place.

The suspension came when the Rocket was leading the NHL in scoring and the Canadiens were battling for first place with Detroit. Richard's suspension also cost him the scoring title, the closest he ever came to winning it. When Richard's teammate Bernie Geoffrion surpassed Richard on scoring on the last day of the regular season, he was booed by the Canadiens' faithful.

Public outrage from Montreal soon poured in. Local radio call-in shows became so inundated with calls that radio stations were begging people not to call in. For his part, Campbell did not budge, and announced that he would be attending the Habs' next home game against the Red Wings in four days. Security was increased at the game, which itself was uneventful. However, it saw many protesters with signs that read "A bas Campbell" or "Vive Richard", with much of the crowd noise directed at Campbell, and few paying attention to the game or to the fact that Richard himself had also taken a seat at the game. As Montreal coach Dick Irvin Sr. pointed out, "the people didn't care if we got licked 100-1 that night."

Midway through the first period, Campbell arrived with his fiancée. Outraged Habs fans immediately began pelting them with eggs, vegetables, and various debris, with more being thrown at him each time the Red Wings scored, who built up a 4-1 lead. The continuous pelting of various objects stopped when a tear gas bomb was set off inside the Forum, not far from where Campbell was sitting.

The Forum was ordered evacuated and Campbell ruled the game forfeited to the Red Wings. The victory would ultimately provide Detroit with the margin it needed to win first place overall and be guaranteed home ice throughout the Stanley Cup Playoffs. Said Jack Adams after the game, "I blame [the media] for what's happened. You've turned Richard into an idol, a man whose suspension can turn hockey fans into shrieking idiots."

The tear gas bomb and forfeiture had also altered the mood of the incident, turning it destructive and violent. A riot ensued outside the Forum, causing $500,000 in damage to the neighborhood and the Forum itself. Hundreds of stores were looted and vandalized within a 15-block radius of the Forum. Twelve policemen and 25 civilians were injured. The riot continued well into the night, with police arresting people by the truckload. Local radio stations, which carried live coverage of the riot for over seven hours, had to be forced off the air. The riot eventually ended at 3 am, and left Montreal's Ste. Catherine street in shambles.

Reporters lined up to see both Campbell and Richard that day. Richard was reluctant to make a statement, fearing that it could start another riot, but eventually gave the following statement:

"Because I always try so hard to win and had my troubles in Boston, I was suspended. At playoff time it hurts not be in the game with the boys. However, I want to do what is good for the people of Montreal and the team. So that no further harm will be done, I would like to ask everyone to get behind the team and to help the boys win from the New York and Detroit. I will take my punishment and come back next year to help the club and the younger players to win the Cup."

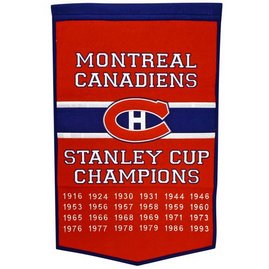

His words would prove prophetic, as the Habs would lose the Cup final to Detroit in seven games, but would win the Cup in the year after - and the four years after that. Richard retired in 1960 after the Canadiens' fifth straight Stanley Cup, a record that still stands.

For more on the Rocket, and the riot on March 17, 1955, check out these links.

Maurice Rocket Richard

Tribute WebsiteCanadian Musuem Of Civilization OnlineMaurice Richard at WikipediaRichard's HHOF ProfileCBC Television and Radio Archives of Richard

Leave Our Richard Alone - NY Times March 17, 1955

The Hockey Game That Broke Out During A Riot - Detroit News

Some schmuck to take Souray's place?

Some schmuck to take Souray's place?