"Hockey is an art," explained Hall of Fame netminder Jacques Plante. "It requires speed, precision, and strength like other sports, but it also demands an extraordinary intelligence to develop a logical sequence of movements, a technique which is smooth, graceful and in rhythm with the rest of the game."

Born January 17, 1929 in Shawinigan Falls, Quebec, Joseph Jacques Omer Plante elevated his trade to a craft, and is remembered not only as one of the National Hockey League's premier goaltenders, but also as an advanced and astute student of the game.

The oldest of eleven children, Jacques' parents encouraged their son's hockey talents, but he was forced to do so using makeshift equipment, including a goalie stick his father carved from the root of a tree.

"I've handled a lot of goalsticks since then, but I'll never forget the thrill of that first one," Plante said, smiling broadly.

Although he played shinny by the hour on the local outdoor rinks, Plante's forays into organized hockey started at the age of twelve.

"I was attending Ecole St-Maurice school in Shawinigan," began Jacques. "Our hockey team consisted of boys seventeen and eighteen years old and I used to watch them play all the time on the outdoor rink. On this one day, I remember it was very cold and I was looking at the game while standing indoors with my back against a stove. The goalie was having trouble and the coach accused him of not doing his best. The goalie was mad and took his skates off. I rushed toward the coach and volunteered to take his place. There was no other goalie around, so I went in the net and played with them the rest of the season."

Always an opportunist, Jacques was playing several years above his age from the beginning of his goaltending career.

"I was standing outside the door of the rink in the Shawinigan Arena where the Shawinigan team (the Cataracts) in the Quebec Senior (Hockey) League played home games. I noticed that they only had one practice goalie and asked the trainer whether I could help out. Although I was fifteen years old by this time, he told me, 'Go away. You're still wearing a diaper!"

Undeterred, that same year, Plante was playing once a week for a team in an industrial league.

"We didn't get paid and my father suggested that I ask the coach for some money," Plante recalled. "The coach agreed to give me fifty cents a game if I didn't tell any of the other players about it. We couldn't afford a radio or luxuries of any kind (in the thirteen-member Plante family). Fifty cents meant a lot to me in those days."

With word of his prodigious talent spreading quickly, Plante was offered an opportunity to play hockey in England for $80 a week. He was also offered a try-out with the Providence Reds of the American Hockey League.

"Each time, my parents turned me down," sighed Jacques. "They wanted me to finish school."

Jacques completed school at the age of eighteen and went to work as a factory clerk, although he continued playing goal virtually every evening. In 1947, he was invited to the training camp of the Montreal Junior Canadiens.

"I got two weeks off from my work to go to Montreal," Plante remembered in a 1969 interview.

"After one week, the Canadiens wanted to sign me but I took one look at the contract and decided to go back home. I was making more money as a clerk!"

Plante spent two seasons with the Quebec Citadelles in the Quebec Junior Hockey League.

"It was during that first year (1947-48) that I heard the Toronto Maple Leafs had put me on their negotiation list, but I really wanted to go with the New York Rangers," admitted Plante.

"Roland Mercier, he was a scout with the Rangers, told me that would be the best move. He said that with the Canadiens, I would be third in line behind Bill Durnan and Gerry McNeil and with the Rangers, I would only have to beat out Chuck Rayner."

It wasn't to be. The Montreal Canadiens signed Plante and assigned him to the Montreal Royals in the Quebec Senior Hockey League, where he played three seasons waiting for his shot at the NHL. At the end of the 1949-50 season, longtime all-star Bill Durnan retired, leaving only Gerry McNeil above Plante in the pecking order of goaltenders for the Canadiens.

In 1952-53, the Canadiens sent Jacques to Buffalo of the AHL.

"That was quite an experience," Plante recalled. "We were in last place, eleven points behind the team in front of us when I got there. We had very few good players. One of the best was Pierre Pilote. We reeled off five victories in a row and attendance in Buffalo jumped from 2,000 a game to 9,000." The Bisons finished that season in last place, but thrust the young goalie into the limelight for the first time. "They started calling me 'Jake the Snake.' I loved all this publicity."

Plante had demonstrated such skill in spite of the Buffalo Bisons' woeful record that the Montreal Canadiens summoned him to the NHL as a standby for Gerry McNeil during the Stanley Cup playoffs. Coach Dick Irvin inserted Plante into the line-up for the sixth game of the semi-finals.

"My knees started to shake," he admitted. "In the dressing room that night, I was so nervous I couldn't tie my skates. Maurice Richard walked over and held out his hands. 'Look at them,' he said. 'They shake before a big game. You'll feel better when you get out on the ice."

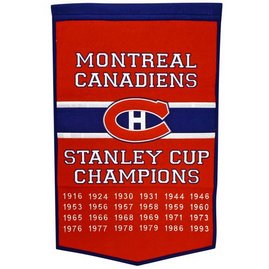

The Canadiens won 3-0 and Plante was back in goal for Game Seven. With the win in that contest, the Canadiens eliminated Chicago to earn a berth in the Stanley Cup final. Plante started Games One and Two, but Gerry McNeil took over in Game Three of the final and the Canadiens proceeded to win the Stanley Cup. Although he played just three regular season games and four post-season contests, the Stanley Cup championship was a sweet victory for Plante; the first of six he would enjoy through his seventeen season NHL career.

The next fall, Plante was returned to Buffalo but with just a month left in the 1953-54 season, Montreal's Gerry McNeil was injured and Plante was summoned to replace him in goal. The Canadiens went to the Stanley Cup final again that spring, with Plante and McNeil both taking their turns. A repeat championship was not in the fates - the Detroit Red Wings took the Stanley Cup that season.

Plante replaced Gerry McNeil as the regular netminder for the Montreal Canadiens in 1954-55. Montreal finished second to the Red Wings that season, just two points behind the leaders. Foreshadowing the success that was to come, Bernie Geoffrion, Maurice Richard and Jean Beliveau finished 1-2-3 in scoring during the regular season. Jacques Plante contributed substantially, introducing a number of plays from the crease that would later label him one of the game's greatest innovators. Much to the dismay of the Canadiens' coaching staff, Plante regularly ventured out of his crease to thwart opponents. He also would leave the crease to harness pucks shot behind the net, assisting his defensemen.

"I was with the Citadelles," he began, explaining when the practice began. "We had four defensemen. One couldn't skate backwards. Another couldn't turn to his left. The others were slow. It was a case of me having to go and get the puck when it was shot into our end because our defense couldn't get there fast enough. The more I did it, the farther I went. It seemed to be the best thing to do, so I did it and it worked." Plante continued, "Possession of the puck is number one. That's all I'm doing, getting control until one of my teammates comes along."

But Plante's pioneering contributions to hockey are most often remembered for being the first goaltender to wear a mask on a regular basis. Jacques had begun wearing a mask during practices in the mid-fifties. After being tripped by Plante during a contest at Madison Square Garden on November 1, 1959, Andy Bathgate of the New York Rangers fired his next shot towards Plante's face to make a statement to the goalie.

"The shot by Bathgate nearly ripped my nose off," Plante fumed.

Badly cut, Plante was escorted to the dressing room for repairs. Montreal's coach Toe Blake was certain that his netminder would be unable to continue playing and asked the Rangers about a replacement goaltender.

At that time, NHL teams didn't carry backup goalies, the home team supplied an emergency replacement as needed. The Rangers employed a thirty five year old handyman at Madison Square Garden named Joe Schaefer as their emergency goaltender. Toe Blake briefly considered using Schaefer in goal, but was not at all confident that the replacement, who had yet to play in an NHL game, was up to the task.

"I told Toe I would only return if I could wear the mask, so there was no choice," explained Plante. Coach Toe Blake was in a bind, and reluctantly agreed. "He never wanted me to wear the mask because he thought it would make me too complacent."

Montreal won the game and proceeded to string together an eighteen game unbeaten streak.

That season, Jacques Plante was awarded the Vezina Trophy for possessing the best goals against average. It was the fifth consecutive season Jacques won the award. It is no coincidence that it was also the fifth straight spring that the Montreal Canadiens won the Stanley Cup.

Yet, even though the extraordinary Canadiens team had evolved into the greatest dynasty the NHL has yet to witness, Jacques Plante never socialized with his teammates. His life was purposely solitary. On the bus, he always sat in the front seat behind the driver away from his colleagues. He stayed by himself in his hotel room, knitting his own undershirts and toques as well as answering fan mail. If a young, aspiring goaltender wrote Plante a letter, Jacques responded with a sheet of fifteen tips to help their game.

"No, I never make friends," Jacques stated unapologetically. "Not in hockey, not elsewhere. Not since I was a teenager. What for? If you are close to someone, you must be scheduling yourself to please them."

Coach Blake and the Montreal management had had enough, and on June 4, 1963, the Canadiens sent their All-Star goaltender to the New York Rangers along with Phil Goyette and Don Marshall, receiving Dave Balon, Leon Rochefort, Len Ronson and Gump Worsley in return.

Plante fumed, disliking New York and his new surroundings. Jacques and the Rangers missed the playoffs both years Plante played in New York, for the first times in his NHL life.

During his second season as a Ranger, Jacques was sent to the minors, reporting for duty with New York's American Hockey League affiliate, the Baltimore Clippers. At the end of that season, Jacques Plante retired from hockey.

But that is not the end of the Jacques Plante story, far from it. After three years of retirement, Jacques was enticed into playing for the St. Louis Blues. The forty year old Plante was teamed up with thirty eight year old Glenn Hall, and the duo performed so well, they shared the Vezina Trophy in 1969.

"I felt I was wanted there and if I feel I'm wanted by a team, I feel good," admitted Plante.

Two years in St. Louis was followed by an unusual three way trade which resulted in Jacques going to the Toronto Maple Leafs. On May 18, 1970, the New York Rangers secured Tim Horton from Toronto. Rangers' GM Emile Francis promised to deliver Plante, who was owned by the Blues, and two minor leaguers to the Maple Leafs.

So, after the playoffs, in a pre-arranged swap, St. Louis sent Plante to New York and the Rangers sent Jacques, along with Denis Dupere and Guy Trottier, to the Maple Leafs. Ironically, Toronto was going through a youth movement at that time, yet the forty-two year old netminder led the NHL with a sparkling 1.96 goals against average in 1970-71 and was selected for the Second All Star Team.

Plante was disappointed to be traded to the Boston Bruins late in the 1972-73 season.

"I've played the best goal of my life the last two years," he stated. "I don't believe it, but it's true."

With Plante playing the final eight games of the season, winning seven for the Bruins, including two shutouts, Boston was able to climb over the Rangers and secure a second-place finish in the East Division.

The fact that the wily goaltender was able to play at all was remarkable. But what was more extraordinary was that Plante was among the best goaltenders in the NHL - all at the age of forty-four.

"At my age, I have to work hard to guard against injuries," mentioned Jacques. His regimen included playing tennis regularly during the summer.

During the season, Plante was fastidious about his exercise routine.

"About an hour each day, I sit on the floor at home in sweat clothes and hook my foot to a chest and drag the chest to me," he explained. "Following this, I usually put my foot on a stool and lift a sixteen-pound weight attached to it. Then, I touch my head to my knee without bending my other knee. I'm always on the look-out for new exercises for my hamstring and groin muscles for it is this muscular area which allows the human body to move from a squatting position to standing with speed and smoothness. I share an interest in the exercise of these muscles with all the body disciplines, but especially ballet where flexibility is as important as it is in hockey."

In February 1972, Jacques had been selected by the Miami Screaming Eagles of the fledgling World Hockey Association in their inaugural General Player Draft. Although he chose to remain with the Maple Leafs at that time, during the summer of 1973, Plante defected to the World Hockey Association, signing a ten year contract to hold the portfolio of coach and general manager of the Quebec Nordiques. Jacques resigned during the season when he heard rumbles that he was going to be asked to replace himself behind the bench.

By the beginning of the 1974-75 season, a second retirement was erased and Plante returned to the crease, this time as a member of the WHA's Edmonton Oilers. At forty-six, he was by far the oldest player in the Oilers' dressing room.

"It reminds me of when I started with the Canadiens," he said. "I could sit and listen all day to older players like Toe Blake and Elmer Lach. Now it's the reverse, I have the floor."

It was an excruciating year for the veteran in which he suffered through serious injuries, including a broken hand and a thumb, and was later felled by an ear injury that caused a loss of equilibrium. One of Jacques' sons was killed in an automobile accident that year, too. The Oilers finished last in their division, although Plante performed well, earning 15 wins against 14 losses and a tie. By October 1975, Jacques Plante realized that time had caught up to him and he retired for good.

"After a long and serious study of my personal position as a player, I decided that I wanted to retire while I was still on top," he stated at that time.

Jacques Plante concluded his career with an incredible career goals against average of 2.38. In 837 regular season NHL games, he won 435, lost just 247 and tied 145. His 82 regular season shutouts puts him fourth on the all time NHL list, behind Terry Sawchuk, George Hainsworth and Glenn Hall. Plante was selected to the NHL's First All-Star Team in 1956, 1959 and 1962, and was a Second Team selection in 1957, 1958, 1960 and 1971. He won the Vezina Trophy a record seven times and was recipient of the Hart Trophy as the NHL's most valuable player in 1962.

Plante was also part of six Stanley Cup championships.

In 1978, Jacques Plante was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Following his retirement, Jacques and his family moved to Switzerland, his wife's homeland, but he returned to the NHL as a goaltending coach first with the Philadelphia Flyers, followed by stints with the St. Louis Blues and the Montreal Canadiens. "I don't want a full time job," he mentioned.

"I'm doing what I like best now, talking goaltending. This has been my life. My reward is seeing a big smile on their (young netminders) faces when they see me around. I don't want any more."

Plante died of stomach cancer in a Swiss hospital on February 27, 1986 at the age of fifty-seven.

Eccentric, exceptional and an extraordinary ambassador to the game, Jacques Plante will forever be remembered for his remarkable contributions to the game he loved.

Also read Jacques Plante And The Legend Of The Mask and Jacques Plante 1952 - 1963

2 comments:

Excellent synthèse, bien illustrée, de la carière d'un athlète phénoménal. Jacques Plante, sans doute, avec Terry Sawchuk, l'un des meilleurs gardiens de buts de tous les temps.

Bravo.

Pierrre Cantin

Chelsea-sur-Gatineau.

My dad and Jacques were cousins. I am trying to locate Jacques Plante's obituary. If anyone out there can help me on this,it would be appreciated. My dad has developed dementia and I would like to find this one item before my dad forgets everything.

Please send answer to rxnn400@gmail.com

Post a Comment