Robert L Note: As all of you who read my site regularly surely know, I have been undertaking the heavy endeavor of documenting the Montreal Canadiens 100 seasons. Close to a dozen posts have been published so far, and I am currently working on the middle 1940's, researching and writing on just about all I can get my mits on that I find interesting. Early this morning I came across this Sports Illustrated interview with The Rocket - Maurice Richard, done late in the 1959-60 season.

The piece, taken from The Rocket's final NHL season, literally, it blew me away!

As I read through it a second time, the human being inside the legend began to emerge and layers were pealed away from what we all always recognized as Habs fans, in Richard, as being a larger than life figure.

Revealing, isn't the word!

The perception that comes out of this article, is of a mortal being, not unlike you and I, who is staring straight at a career crossroads.

I could have saved this for the 1959-60 season post, but the interview to me, felt like a piece of history that stood alone, beyond the Montreal Canadiens story.

I immediately felt that it had to be shared amongst fans!

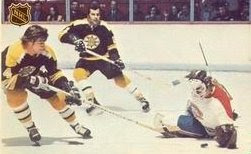

The SI feature link has no photos attached, so again I went digging through my files and folders for shots I felt would bring the piece to life. I hope you enjoy this glimpse inside The Rocket's heart and mind, in early 1960.

I wish to dedicate this post to all of you younger Habs fans out there. I urge you to find the time to dive headlong into your favorite hockey team's history. It will not only bring you a greater appreciation for the team, it might just springboard you into your grandfather's life and times.

One Beer For The Rocket

One Beer For The RocketMaurice Richard, the violent Canadien, watches his temper and his weight in his 18th year of ice hockey

"What makes Toronto tick?" asked the TV announcer.

"What makes Toronto dead?" Maurice (The Rocket) Richard asked back.

Richard, who has played right wing for the Club de Hockey Canadien Inc. every winter since 1942, sat, his shoes off, in a dark room in the Royal York hotel, laughing at Red Skelton and smoking a cigar - a burly man of 38 with an erect carriage, tilted, somber, devout face, inflexible eye, abundant black hair which also thickly mats his chest and back, making him look like a mangy bear, and queer, thin, knobby legs.

"If he had another hair on his back, he'd be up a tree," says Kenny Reardon, who is vice-president of the Montreal Canadiens.

Richard's roommate in Toronto, Marcel Bonin, who once wrestled a toothless, suffering bear in a carnival ("I never win," he admits) was out somewhere in the cold, solid city. The Ontario Good Roads Association made roisterous marches up and down the long, dim hotel corridors, X's on the backs of their red necks and violent apocalypses on their broad neckties. One of them hammered on Richard's door.

Richard's roommate in Toronto, Marcel Bonin, who once wrestled a toothless, suffering bear in a carnival ("I never win," he admits) was out somewhere in the cold, solid city. The Ontario Good Roads Association made roisterous marches up and down the long, dim hotel corridors, X's on the backs of their red necks and violent apocalypses on their broad neckties. One of them hammered on Richard's door."Go to bed, damn it!" Richard shouts.

"That's my whole life trouble," he said, "trying to sleep. My mother was the same way. If I sleep four or five hours a night, it's good. TV puts me to sleep every time. Where would we be without TV, eh? And what did we do before?

"Eighteen years of this," he said. "In the town. Out of the town. I really get tired of all these trips." He got up and closed the transom, shutting out the racket. "People bother me," he said. "The young ones, they're all right. It's the old ones who have had a drink or two too much, yelling at you, asking all sorts of questions."

He made a face.

"I was at this sports banquet. A famous person got up to speak. He had too much to drink, like James Dean in that movie. He kept on talking and no one knew how to stop him. It was embarrassing. I'll never be like that."

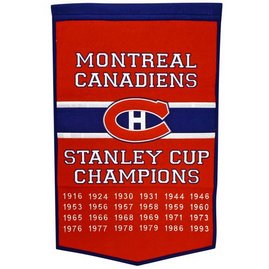

And no one, certainly, will ever be quite like Maurice Richard, who next week, as their captain, leads the Canadiens toward their fifth consecutive Stanley Cup. Not even himself.

And no one, certainly, will ever be quite like Maurice Richard, who next week, as their captain, leads the Canadiens toward their fifth consecutive Stanley Cup. Not even himself. "You should have come up five years ago," he had said in the men's room of a Montreal - Detroit sleeper several days before, where he has sat so many nights reading until the porter fills the room with hockey players' shoes.

"It's getting to be my time now. I'm getting near the end. I have had some good times, some bad. I started out with three bad injuries [fractured left ankle, left wrist, right ankle] and am ending with three bad injuries [sliced Achilles' tendon, fractured left tibia, depressed fracture of facial bone]. The old days are gone. These are the new days. I'll never score five goals in one night."

He looked out the window at the dismal, glaring snow, listening to the wheels as the train bore him to his 1,091st game. Behind him, the glorious past, the records: 50 goals (and in a 50-game season); five goals in a playoff game; 18 winning goals in 14 playoff series, six of which were in overtime; 26 hat tricks (three or more goals in a game); 618 goals; 1,076 points; at least one goal in nine straight games; etc.

"He was a wartime hockey player," says Frank J. Selke, the 66 year old managing director of the Canadiens. "When the boys come back, they said, they'll look after Maurice. Nobody looked after Maurice. He looked after himself. When the boys come back, they said, they'll catch up with him. The only thing that's caught up with Maurice is time."

"It's changed. I'm the oldest; the rest are kids," Richard said one night in a Detroit bar which advertised a stereophonic juke box. ("I'd go where the boys go," he had said, "but it's not a nice place. This is a quiet little bar on the corner.") "I know I'm not playing good hockey now. I'm weak now. My legs are tired. After a minute and a half, I'm tired. I'm so tired. I will try to diet. I weigh 194 pounds. I've been playing at that weight for the last five years, but I'm so heavy I'm floating on air. I got to take off five or six pounds before the playoffs. Only one beer. That's all I'll drink. I'll drink gin. That isn't fattening."

He watched on TV a tape of the game he had played in an hour earlier. He had scored two goals. The bartender got in front of the TV set while he scored the first goal and Richard did not see it. He was told he had been chosen the game's outstanding player. "Me?" he said. "I don't believe it. I did not deserve it. Luck."

"If I can wake him up!" Selke says. "He kids himself that if he's feeling well, he's at the right weight. You don't feel well at the right weight. You're crabby. But he makes so much money! ( Richard 's salary is estimated at $30,000.)

He's wonderful to sign," Selke says. " 'How much do you want?' I ask. 'How much do you want to give me?' he says. I always give him a little more than anyone else I hear about through the grapevine. He has done so much for the game."

He's wonderful to sign," Selke says. " 'How much do you want?' I ask. 'How much do you want to give me?' he says. I always give him a little more than anyone else I hear about through the grapevine. He has done so much for the game." Richard 's annual income has been estimated at $60,000, total worth at $300,000. He is a public relations man for Dow Brewery and Quebec Natural Gas, has part interest in a store which sells gas appliances, has bought a tavern which he is calling No. 9 after his uniform number and referees professional wrestling matches.

"They're smart guys, the wrestlers," he says. "Ninety percent of them are educated. I know most of the guys. I like them. I wrestle a lot with Boom Boom [Geoffrion] in the room. Do a lot of crazy things."

"I've been in hockey 53 years and I've never had an aging athlete admit he was through," Selke says. "He misses passes he never missed. He tops the puck like a golfer. He never did that. He's got too big in the middle. I'd bench him. He'd damn well get in shape. I wouldn't sign him for another year. I wouldn't let him make a fool of himself in front of a crowd."

Richard had played ineptly the night before, and Selke, like a proud, rigorous, loving father, spoke not in intemperate anger but with old, gruff affection, hurt by loss and memory. If his Maurice wanted to play next year, he would probably relent.

"If I make bad," Richard says, "people will talk. I like to leave the game before people criticize me, boo me. When I'm ready, I'll go tell Mr. Selke. Fifty percent of goals are luck. You have to work for the others. I used to be like that. I lost all that. I used to skate a little better, go around the fence a little better. I've got to watch myself. I don't want to get another accident. The day of the game I'm afraid to get hit. I know when I feel that it is getting close to the end. Everyone should wear helmets. It's just up in the mind. It would be a good thing. It's a dangerous spot, the head. We've tried; they bothered us, were too warm. But if everybody wore them it would be the same.

"I have to work so hard all the time," he says. "When a guy is a natural he doesn't have to drive and force himself. Some guys.... If Howe would work a little harder, he'd be better."

"He used to be a whirlwind," says Gordie Howe of the Detroit Red Wings. "Now he's just a whirlwind half the time. But when he's not doing a lot, you notice it. Not like the others."

"I'm a little too old to be called Rocket," says Maurice Richard.

"I first saw him in 1942," says Reardon. "I was playing for an Army team. I see this guy skating at me with wild, bloody hair the way he had it then, eyes just outside the nut house. 'I'll take this guy,' I said to, myself. He went around me like a hoop around a barrel. 'Who's that?' I asked after the game. 'That's Maurice Richard,' the guy said. 'He's a pretty good hockey player.' 'Yes,' I said, 'he is.'"

"I first saw him in 1942," says Reardon. "I was playing for an Army team. I see this guy skating at me with wild, bloody hair the way he had it then, eyes just outside the nut house. 'I'll take this guy,' I said to, myself. He went around me like a hoop around a barrel. 'Who's that?' I asked after the game. 'That's Maurice Richard,' the guy said. 'He's a pretty good hockey player.' 'Yes,' I said, 'he is.'""When he's worked up," says Selke, "his eyes gleam like headlights. Not a glow, but a piercing intensity. Goalies have said he's like a motorcar coming on you at night. He is terrifying. He is the greatest hockey player that ever lived. I can contradict myself by saying that 10 or 15 do the mechanics of play better. But it's results that count. Others play well, build up, eventually get a goal. He is like a flash of lightning. It's a fine summer day, suddenly...."

"Holy Dirty Dora!" says Montreal coach Toe Blake. "You got to give it to the fellow. The fellow was fantastic. That's why you got to give it to the fellow. That will!"

"In all my experience in athletics, academic pursuits, business," says National Hockey League President Clarence S. Campbell, "I've never seen a man so completely dedicated to the degree he is. Many people who prosper take prosperity for granted. He doesn't to this day. He is the best hockey player he can be every second. You know, he is the eldest of a fairly extensive family raised in relative poverty. Back of it all, somehow or other, he was going to lift himself, one way or another. He has an inner urge to transcend."

"He is not the Pope...." says Camil Desroches, the Canadiens' publicity man, wistfully.

"He is God," says Selke.

Richard is regarded in Canada as no athlete is in the United States. He is not only a sports idol, he is the national idol, particularly among the French speaking people of Montreal and the province of Quebec. When Maurice Richard scores a goal in the Forum, even an insignificant goal in a meaningless game, it touches off a unique celebration. First, an astonishing, prolonged din of cheering and applause, then newspapers, programs, galoshes, hats are thrown onto the ice. Richard skates in abstracted, embarrassed, lonely circles through the heavy snow of objects. The game has to be stopped until the attendants clear the ice. But adulation sits on him like an uneasy crown.

"Nothing goes in my head," he says. "I don't believe in anything. It's nice. I like to forget about it. I don't think I deserve it. That's my whole trouble all the years. It's just the way it went. There are better hockey players but they don't work as hard. I like to win."

"We were playing Toronto once in a benefit softball game," Selke says. "Instead of just using the Maple Leaf players, they used the best softball players they had in their entire organization. They were beating us 25-5. Maurice was playing third base. Someone laughed about the score. 'You might think it's funny getting licked 25-5 in front of 14,000 spectators,' Maurice said to him. 'I don't think it's a bit funny.' "

"I never did like to see anybody laughing," Richard says, "making a farce out of something. I don't like to lose. They won't forget about me but when they stop writing about you, when they stop talking, it won't be the same. It will be a different life. I like to meet people, but not to talk about hockey when we had a bad game and lost. I stay away from everybody and go home. That's why I like fishing, to be quiet. When I'm traveling around the provinces I go fly fishing for an hour or two at night. Hunting is nice, too, because I like to be in the woods. They all talking about you but I don't like it. In front of me, it feels funny. Another player, they wouldn't have done it. But I'm afraid to let the French people down. That's why I'm worried out. Before, I could work hard, follow everybody. I don't want to be kept on the ice through sympathy."

"He is more important than the cardinal or Duplessis," explains one fan. "There are many cardinals. Duplessis was only the head man of Quebec. Maurice Richard was not only the best of the French but of the English as well. He came to epitomize the desire of superiority of the French Canadian nationalists. He was one of their best expressions. But you must understand that he has no personal interest in it. Maurice Richard never did a thing to accentuate it. He was a person to fix their eyes. Here was a demonstration."

While an idol, Richard has also been a figure of controversy. He fought a lot on the ice, violently and well, although the sight of blood makes him ill. "I see myself bleeding or anyone else bleeding," he says, "I feel funny. Once I cut my hand as a little kid and I passed out." In 1955, after a series of incidents culminating in the slugging of a linesman, Campbell suspended him for the last three regular season games and the playoffs. That decision caused the notorious Forum riot and inspired a ballad to the tune of Abdul Abulbul Amir:

While an idol, Richard has also been a figure of controversy. He fought a lot on the ice, violently and well, although the sight of blood makes him ill. "I see myself bleeding or anyone else bleeding," he says, "I feel funny. Once I cut my hand as a little kid and I passed out." In 1955, after a series of incidents culminating in the slugging of a linesman, Campbell suspended him for the last three regular season games and the playoffs. That decision caused the notorious Forum riot and inspired a ballad to the tune of Abdul Abulbul Amir:Now our town has lost face

And our team is disgraced,

But these hot headed actions can't mar

Or cast any shame on the heroic name

Of Maurice (The Rocket) Richard.

Richard has also been called aloof, sullen, moody, peculiar, uncommunicative, tight. "I'm unpredictable," says Richard , cheerfully.

"He is difficult with difficult people," says Junior Langlois, a teammate.

"His difficulty was the language barrier, a very modest formal education and the disparagement of no war service," the fan says. "He was tagged with aspersion."

"Somewhere at the back of his mind," says Selke, "there is a feeling that someone is trying to put it over on him. He has a tremendous dread of poverty."

"You can say that again," Richard says, laughing.

"You can say a lot of things to Maurice," Selke says, "but you got to be careful of your adjectives. Maurice just can't take anything. If he could, he would not be Maurice Richard. Frenzy makes him! But there is no meanness in Maurice Richard. He's 100% solid gold; someone you'd be proud to have as the husband of one of your daughters; faithful, devoted."

"For 15 years he's been a law unto himself," Reardon says. "He has been so good he didn't have to do the things others did. The time hasn't come when he realizes he's human and has to do the things everyone else does. But if he wasn't so obstinate, he couldn't have done the things he has done. He was watched, watched, watched until he finally blew. There are more sly ways to get at a man with the stick. The stick stings. You know who gave it to you. When he blew, he blew good. No one could have taken it as long as he did and done less about it."

"It's different," says Richard . "Today they don't have to bother me like before. But every fight I've been in, every suspension, I was not the first. I'm not the type to hit a guy. Many times I don't like a guy, but I get on the ice I forget all about it. Now it's no use to fight. Ten minutes, $25 fine. If you keep fighting too long, they send you out. It's a match penalty, $100 fine!"

"I told him," says Selke. "You don't prove anything at your age to take on a young buck. You win? You've won so many fights already. You lose? They'll say you let a bandy rooster lick the cock of the walk."

"I am a very quiet man," says Richard. "At the beginning of my career I didn't know what the English people were talking about. Even today, I like to go somewhere and want to go somewhere, but they ask me to make a speech. I like to, but I am a man of few words."

"I am a very quiet man," says Richard. "At the beginning of my career I didn't know what the English people were talking about. Even today, I like to go somewhere and want to go somewhere, but they ask me to make a speech. I like to, but I am a man of few words.""Richard the sphinx!" says Reardon. "He used to ride all the way to Chicago, sitting in the corner. He didn't even read a book. Henri, his brother, was that way, too. After Henri had been with the club two years, a reporter asked the coach if he could interview him. 'Sure,' he said, 'go ahead.' 'Does he speak English?' the reporter asked. 'Hell,' said Blake. 'I don't even know if he speaks French.' Maurice is just a great company man. He shows up for the game. Does a great job and disappears into his shell."

"He's like the lion who's let out of the cage twice a week," says Selke's son, Frank Jr., the Canadiens' public relations man.

Richard's cage is a spacious one story house by the Back River on the rim of Montreal . "I have six kids," he says. "One for each 100 goals. If I have to reach the 700 mark, I'll have to get another one, but I think I'll have to stop. I mean, there's no more on the way yet. My oldest is Huguette. She is 16 and studying to be a beautician. All she does now is ski. She doesn't do her skating anymore. I'd like to do figure skating too, but I'm embarrassed. Then there is Maurice Jr., who is 14. He's good at school. Not too bad. He's a fair hockey player, right wing. He wants to play hockey, too. He is an inch and a half taller than me. Normand is 9. This one is the one that likes every sport. A right wing, too. He's a natural. Just fair in school. Then André, who is 5. He is starting to go to school this year. He's kind of young, but he's all right. Suzanne is 2 and Paul, we call him Paulu, is one. My wife Lucille has missed only two hockey games in 18 years. She was sick for a week this year."

Richard's cage is a spacious one story house by the Back River on the rim of Montreal . "I have six kids," he says. "One for each 100 goals. If I have to reach the 700 mark, I'll have to get another one, but I think I'll have to stop. I mean, there's no more on the way yet. My oldest is Huguette. She is 16 and studying to be a beautician. All she does now is ski. She doesn't do her skating anymore. I'd like to do figure skating too, but I'm embarrassed. Then there is Maurice Jr., who is 14. He's good at school. Not too bad. He's a fair hockey player, right wing. He wants to play hockey, too. He is an inch and a half taller than me. Normand is 9. This one is the one that likes every sport. A right wing, too. He's a natural. Just fair in school. Then André, who is 5. He is starting to go to school this year. He's kind of young, but he's all right. Suzanne is 2 and Paul, we call him Paulu, is one. My wife Lucille has missed only two hockey games in 18 years. She was sick for a week this year."Richard adores children and is, perhaps, most at ease with them. He always carries postcards with his picture on them which he signs and gives away. Children adore Richard . If they are not French, he asks them if they speak French. If they do, they proudly and hurriedly say their few words of high school French and flee with their autographs.

"I never wanted to have a fan club," Richard says, "because of the exploitation. I have fans but no clubs. Instead of the kids spending money on us, let us spend money on them."

Richard often skates with kids or referees their games. "The kids all call this one place where we skate Maurice Richard Park," he says. "That's not the real name. In Montreal most of the people things are named after are dead people. Parents should spend more time watching their kids play," he says. "I come out after the game starts and stand hidden in a corner. I like to play with them in the park. The kids get such a kick out of it. They talk of nothing else for a week afterward."

One night in Detroit several weeks ago, Richard sat at the bar in a steak house with some businessmen friends. "When I got friends," he says, "I keep them and stay with them all the time." He had been telling his friends about Varadero Beach in Cuba, groping for words to describe its beauty. "The wife and I were swimming 50 or 60 feet offshore," he said. "Fish of all different colors came around us and touched our legs. The wife got scared. It was so beautiful. The water was all different colors—" Suddenly he stopped and drank his screwdriver. "You never know what you want to do in life, eh," he said. "I'm fed up with hockey, I don't want to skate anymore."

"You said that last year," a friend said.

"And four years ago," Richard said, and smiled thinly.

"No, I'm not fed up with hockey," he said, as he walked back the dark blocks to his hotel through the snow in his deep blue overcoat and a hat with a red feather in the band. "That's my living. I'm fed up with the traveling, the fear of accidents, the...I...good night," he said, "I'm going to watch The Late Show until I get sleepy."

There is a poster on the wall of the Canadiens' dressing room in the Forum. It is a quotation from Abraham Lincoln. It reads, in part, "I do the very best I know how, the very best I can, and I mean to keep on doing so until the end."

"I read that almost every game," Richard says. " Dick Irvin (the late Montreal coach) put that up. It's right in front of me."

At the NHL meeting last year there was some facetious talk of the end, the day when Richard would get so old Montreal would no longer protect him and he would be available for the $20,000 waiver price. "I'd pay $20,000 for him," said Phil Watson , then coach of the New York Rangers. "I'd put him in a glass case in Madison Square Garden and say, 'Pay your money and take a good look at the great Maurice Richard!' "

.

1 comment:

That was an absolutely fantastic article, one of the best things i've read in my life. One thing has me bothered though. I wonder what his unfinished sentence when he got back to his hotel room was?

Post a Comment