Jacques Plante wasn't the first goaltender to wear a mask in an NHL game - credit for that goes to Clint Benedict of the Montreal Maroons in 1930 - but Jake the Snake popularized the facial protection for netminders when he wore one on Nov. 1, 1959 against the New York Rangers, having been struck and badly cut in the face by a backhand off the stick of Rangers' Andy Bathgate.

Montreal Maroons goalie Clint Benedict with a primitive mask idea, made of metal and leather, that he briefly wore in 1930. Benedict found that the nose of the mask obstructed his view of pucks at his feet and discontinued wearing soon after.

The Plante mask was some time in the works, and the goalie wore it regularly in practice before finally telling coach Toe Blake he wouldn't return to the ice that November night unless he could wear it. Blake relented, the Canadiens won, and the face of goaltending was changed forever.

Al McKinney holds a plaster mold of his face used during the development of Plante's fiberglass mask, which was first used in 1959. In McKinney's left hand is a mask made during the early 1960's by Plante's company. The photo was taken by John Mahoney of the Gazette.

Montreal Gazette sports columnist Dave Stubbs sat down with Al McKinney of Lachine, Quebec and spoke with him about his considerable role in the production of Plante's first game-worn mask, which looked like it came out of the Phantom of the Opera.

Goalies everywhere owe a debt of gratitude, and at least a few teeth, to the contribution of McKinney whose mug was plastered by inventor Bill Burchmore during the development of a mask for Canadiens goalie Jacques Plante. Here's the article published March 4, 2006.

Molding An NHL Legend, by Dave Stubbs

The real star in any mad scientist movie isn’t the deranged guy with the evil laugh and the hair styled by sticking a nail file in the light socket. In fact it’s his blindly loyal assistant who might volunteer for the crude experiments that will result in either his own dreadful demise, or a discovery of history-altering proportions.

Enter Lachine’s Al McKinney, until now the unknown Igor to whom every hockey goaltender of the past five decades owes a few of their own teeth.

Almost 50 years ago, face caked in a thick plaster, straws inserted up his nostrils so he wouldn’t suffocate, McKinney surrendered himself to Bill Burchmore, a sales and promotion manager at Montreal-headquartered Fiberglas Canada Ltd.

Then, on Nov. 1, 1959, Canadiens goaler Jacques Plante skated onto Madison Square Garden ice behind a fiberglass mask. He was the NHL’s startling answer to Lon Chaney in the 1925 horror film Phantom of the Opera - or, of a more recent vintage, Anthony Hopkins’s Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs.

"I designed the mask for protection, not for good looks," Burchmore said in a 1959 Gazette interview. "It has all of Jacques Plante’s facial features. If it was made for Clark Gable, it would look like Clark Gable."

That November night, with his uncommon flair for the dramatic and, fittingly, in the shadows of Broadway, Plante forever changed the face of the goalie.

If the late Burchmore is the father of the modern-era mask, then Al McKinney, 74, remains a vital branch on the family tree.

For it was McKinney’s gentle mug onto which Burchmore first ladelled his plaster in the late 1950s, this facial mold beginning Burchmore’s development of Plante’s first game-worn mask.

The future Hall of Fame goalie popularized the use of the mask, introducing it in New York when he was carved for seven stitches by a backhand off the stick of the Rangers’ Andy Bathgate.

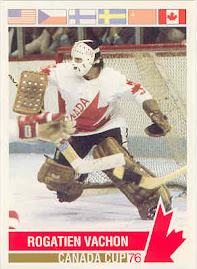

But Plante was not the first to wear a mask. Nor can the honour go to the Maroons’ Benedict, who usually gets credit for the couple of games in 1930 during which he strapped on a crude protector to shield a broken nose and cheekbone.

Credit for the first mask in organized hockey goes to Elizabeth Graham (middle in photo, without mask), goalie for the Kingston Queen’s University women’s team, who wore a fencing mask in 1927. As the Montreal Daily Star reported at the time, Graham "gave the fans a surprise when she stepped into the nets and then donned a fencing mask."

Plante had been toying with a mask in practice through the ’50s, cutting a broad eye-hole in a plastic shield made by Delbert Louch of St. Mary’s, Ont. Hailed as "the shatterproof face protector for all sports," the Louch shield never caught on, leaving the forehead exposed and fogging up in frosty arenas.

Bill Burchmore was at the Forum for a playoff game in April 1958 when a barefaced Plante was drilled in the forehead by a puck. In the NHL’s single goalie days, the contest was delayed 45 minutes while he left for repairs.

Burchmore returned to his office the next day and gazed at the fiberglass mannequin on his desk. Before the bulb of inspiration dimmed, he wrote to Plante to tell the goalie he could make him a space-age mask - and this almost before the space age.

Plante’s initial indifference did nothing to dampen Burchmore’s enthusiasm. And it’s here that McKinney, then an eager sales trainee with Fiberglas Canada, enters the picture.

"Bill asked me one day, ‘Can you stay after work and give me a hand with a project? I’m doing something for Jacques Plante,’ " McKinney recalled this week.

Habs coach Toe Blake shows a sense of humour, finally, about Plante's insistence on wearing the mask.

"It didn’t faze me at all when he told me I was going to be his model for a face mask.

McKinney had his eyes covered and straws inserted in his nostrils, then sat motionless as Burchmore smoothed the plaster over every pore, from his hairline to his jaw. It took a half hour for the compound to harden on the face of a man who suffered from claustrophobia.

"A little scary," McKinney admitted. "At least I could breathe."

What Burchmore had not done was first apply a release agent, like a petroleum jelly. Both men realized the oversight when the hard plaster held fast.

"Bill pulled and pulled, and he had to take a break every 10 seconds," McKinney recalled. "He was pulling at my forehead, and the mold wasn’t moving. I was wondering what would happen when he reached my eyebrows.

"As he got lower, he pulled every whisker on my face. It was pretty grim. We laughed about it later. Well, Bill did, anyway."

It took an hour for the removal. McKinney compared it to 60 minutes of pulling adhesive tape off hair on the skin.

"The next day we came to work as usual - my face might have been a little red - and I never saw the ongoing process that created the mask," he said. "I probably saw the finished product for the first time on TV."

To convince Plante of the idea, Burchmore needed both the McKinney mold and his own skills as a salesman.

"Just about everyone thought I had rocks in my head," the inventor said at the time.

Plante’s face was molded before the 1959-60 season at the Montreal General Hospital under medical supervision, a woman’s nylon stocking slipped over his head to avoid a repeat of the McKinney torture.

Next, Burchmore produced a stronger mold of poured gypsum. From this came the famous "phantom" mask, 3/16ths of an inch thick and weighing 14 ounces, made in his Town of Mount Royal basement by layering polyester resin-soaked fiberglass cloth over the mold of Plante’s face.

And then he tested it, striking the mask with a steel ball swinging on a pendulum to simulate the force of a Bernie Geoffrion slap shot. He couldn’t damage it.

The finished product stunned, even horrified, players and fans when Plante wore it into action.

Burchmore’s 54-year-old son, Steve, recalls being dinged in the forehead around that time while playing goal in a minor-hockey game in Montreal.

"My dad told me, ‘If I can keep Plante pretty, then I can do the same for you,’ " he said. "So he molded my face and made me a mask. But I finally smartened up. I became a winger."

A confident Plante was brilliant in goal, winning 10 and tying one in his first 11 masked games, yielding just 13 goals.

Burchmore quickly developed the "pretzel" mask, using wound yarn of fiberglass instead of solid sheets. It shaved away nearly four ounces and increased comfort with its ventilated design.

An innovator himself, Plante later began mass-producing his own masks of high-impact fiberglass and epoxy resin at Fibrosport, a company he established in Magog. His 1970s models retailed for $12 to $18, while he sold a pro style, similar to what he wore at the end of his NHL career, for $22.50.

McKinney never met the goalie whose life he helped change. He skated for the junior Montreal Royals as a teen, suiting up at the Forum against Jean Béliveau, Bernie Geoffrion and Dickie Moore, and once flattened Canadiens Canadiens legend Maurice Richard, off the ice.

Having injured his tailbone in a practice, McKinney was asked by a team doctor to bring a urine sample to the Forum the next day for precautionary analysis. The Rocket nearly expired in laughter when the earnest kid, who’d never before been asked for a specimen, arrived from home with a quart milk bottle that he’d filled to the top.

McKinney is now semi-retired from the insurance business and still plays hockey (not goal) twice a week in Ste. Anne de Bellevue with oldtimers from Hudson.

He has often paused to consider his role in hockey’s evolution. This week’s Gazette story on a Plante memorabilia auction again sent him in search of the mold, its white plaster lacquered a ruddy colour by Burchmore.

What looks back at him is the face of a man in his 20s, exquisite in detail, the finest creases in his complexion clearly visible. McKinney had long ago screwed a hook in the back, and his mug hung on a wall until finding its way into a bureau drawer.

Such remarkable hockey history, buried out of sight? He laughed as he carefully wrapped the mold back in a white cloth.

"Maybe my wife hid it there," he said. "And she’s probably looking for this rag."

Jacques Plante’s first mask in 1959 was as effective at protecting him as it was scaring fellow players and fans.

Here’s how the writer Arturo F. Gonzales Jr. described it in a feature titled Hockey’s Faceless Wonder, for the November 1960 issue of Modern Man magazine:

"Crouched in the cage with the sun white glare of hockey rink floodlights carving his artificial ‘face’ into deeply shadowed eyesockets and a gaping hole of a ‘mouth,’ Plante looks like something out of a horror film.

"And when he uncoils and catapults from his cage toward an opposing player, his body exaggerated to twice its normal bulk by the thick padding of his uniform, his image stirs butterflies in the stomach of his target.

"His glittering razor-sharp skates shattering the ice at hellbent speeds combine with the scimitar-like brandishing of his stick to create an effect which unnerves even the leathery veterans of the sport."

This article, written by the late Pat Curran appeared in the December 12, 1959 issue of the Montreal Gazette.

Due to the picture of the page being clipped near the bottom, I was unable to print all of the text.

Mount Royal Inventor Comes To Goalies Aid, by Pat Curran

That old mother's lament, "I'll never raise my son to be a goaltender" may soon be a cry of the past.

Thanks to Bill Burchmore, an inventive fibre glass salesman, and Jacques Plante, the colorful Canadiens custodian, the most dangerous and difficult position in hockey is could become the safest, and the easiest.

Burchmore inventended the mask that appears to have ended the search for facial protection sought by goalies for more than three decades. Tested under National Hockey League fire by the brilliant Plante, the moulded mask is now being used by other professional netminders, while orders are being received from amny parts of Canada and...

....to discard it due to limited visability.

Since then, several unsuccessful attemps have been made to design a protector. Visability was the stumbling block in each case.

Probably the most ingeneous netminder ever to toil in big time hockey, Plante began his hunt four years ago after he suffered a broken cheekbone. He came uo with a bulky plastic contraption which he was able to use in practice but was unsuitable for league play. two years ago, in a pre - game workout, Jacques suffered another face fracture. It was after this injury that W. A. "Bill" Burchmore took an active interest in the invention of his mask....

The four time Vezina Trophy winner was immediatly interested, but somewhat disturbed when the young inventor explained his ideas.

"Jacques thought that I'd perfected the cage type mask", says Burchmore. "He didn't understand plastics and thought I was crazy when I told him it would have to be molded ifit was going to be any good."

"As a matter of fact", recalls Bill, "Just about everyone thought I had rocks in my head. Afterwards I had developed....

Back in his basement again, Burchmore experimented with a steel ball and a pendulum until it reached the force of a Beliveau, Geoffrion, Howe, or Bathgate. Satisfied after numerous tests, Burchmore called Plante to tell him the results.

"Jacques must have broken all speed limits getting here", says Burchmore. "He was aroused and about as happy as a little boy who has just been given his first pair of skates. But I was happy too, I had spent $1500.00 on the thing."

....perspiration than a catcher's cage. The dull colored protector is better than plexiglass in that it causes no shadows and no glare from the rink lights and doesn't fog up.

"The greatest advantage is that it will eliminate 99 per cent of injuries", says Burchmore, proudly.

Why not 100 percent?

"Because", cautions Bill, "nothing is perfect. There is always the longshot chance of a skate getting through the small slots for the eyes and mouth."

While Plante was satisfied with the mask in training camp, club brass were not in favor of him using it in regular play. Coach Toe Blake apparently....

....namely Gil Meyer of Cleveland and Gordie Bell of Belleville McFarlands have been using the mask while three or four handicapped youngsters have been fitted for it. Muzz Patrick, New York general manager has ordered all junior and juvenile goalies in the Rangers chain to wear them.

"I'm convinced that the masks are here to stay", says Patrick, "Our young players might as well get used to them."

Burchmore has also been contacted for details by the Russian Embassy.

Present cost of the mask for which Bill Burchmore has applied for a patent is $300.

Also read Jacques Plante One On One and Jacques Plante 1952 - 1963