It was the Montreal Canadiens ninth season of existance, and the NHL as we know it, was about to be born.

The Canadiens were not yet known as "the Habs", "Les Glorieux" or "Le Tricolore", and the term "Flying Frenchman" was only beginning to spread. In fact, the Canadiens were just another professional hockey team in what was then a rapidly growing sport.

Albeit just two years removed from their first Stanley Cup championship, the Canadiens team and franchise of the day were possibly best recognized at the time as the one professional city hockey team made of mostly of french speaking players. It was their calling card upon their 1909 creation, and remained their identity and public perception despite the fact that they had been signing more and more players from outside the province of Quebec in order to maintain it's survival.

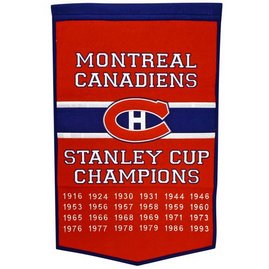

Up until 1917, teams in the city of Montreal had won no less than 17 Stanley Cups since 1893. In the 24 years since Lord Stanley of Preston donated the trophy that was to be competed for in the dominion of Canada as a challenge cup, the city of Montreal was for all intents and purposes, the center of the hockey universe.

Prior to the forming of the NHA in 1909, the Stanley Cup remained an amateur team's conquest. It's winners were:

Montreal AAA: 1893, 1894, 1895 (March), 1902 (March), 1903 (February)

Montreal Victorias: 1895, 1896 (December), 1897,1898,1899 (February)

Winnipeg Victorias: 1896 (February), 1901,1902 (January)

Montreal Shamrocks: 1899 (March), 1900

Ottawa Senators (Silver Seven): 1903 (March), 1904, 1905, 1906 (February), 1909

Montreal Wanderers: 1906 (March), 1907 (March), 1908

Kenora Thistles: 1907 (January)

From the formation of the NHA until the beginning of the first NHL season, the Stanley Cup was competed for by teams across Canada. The winners during those 8 years were:

Montreal Wanderers: 1910

Ottawa Senators: 1911

Quebec Bulldogs: 1912, 1913

Toronto Blueshirts: 1914

Vancouver Millionaires: 1915

Montreal Canadiens: 1916

Seattle Metropolitans: 1917

Since the Stanley Cup had been donated to the country and competed for since 1893 there had been 31 winners in 24 hockey seasons. The Montreal Canadiens had been but one of the 12 clubs to win the Cup. Other teams in the city of Montreal had already claimed 16 Stanley Cup championships when the NHL began in 1917-18

Since the Stanley Cup had been donated to the country and competed for since 1893 there had been 31 winners in 24 hockey seasons. The Montreal Canadiens had been but one of the 12 clubs to win the Cup. Other teams in the city of Montreal had already claimed 16 Stanley Cup championships when the NHL began in 1917-18The game of hockey, and Stanley Cup competition, had gone through many changes in it's 24 years evolution. It had essentially evolved from an outdoor game of shinny to an indoor business capable of seating up to 7,000 paying customers in those years. However rudimetary it seems when looking back now, it became a business long before the NHL was formed. The NHA seasons from 1909 to 1917 were merely a template for what professional hockey would later become.

In all the constant change and flux of the earliest days of pro hockey, the Montreal Canadiens were nothing more than another pro hockey franchise dealing with the survival constraints brought on by the first world war. The Canadiens, by this time, had identifiable stars in Newsy Lalonde, Didier Pitre, Georges Vezina, and Jack Laviolette, and these early hockey pioneers helped forge an identity for the team among hockey fans in Montreal.

In all the constant change and flux of the earliest days of pro hockey, the Montreal Canadiens were nothing more than another pro hockey franchise dealing with the survival constraints brought on by the first world war. The Canadiens, by this time, had identifiable stars in Newsy Lalonde, Didier Pitre, Georges Vezina, and Jack Laviolette, and these early hockey pioneers helped forge an identity for the team among hockey fans in Montreal.As pro hockey evolved, so did society. Times were moving fast, and they were hard times. Financial gain and prosperity for those willing to risk it all when investing in hockey were obtainable for the most daring of folks, but the circumstances of failure loomed large. Due to the times, it was so with any financial endeavor. Hockey was but another fleeting opportunity for financial prosperity in 1917. Fans of the game then, and the money makers and the visionary risk takers of the day interested in hockey pourred the foundation for what the game is today.

The Senators, Wanderers, and Canadiens were three of seven teams present when the NHA formed in 1909 that were still viable when the NHL began in 1917. Montreal would outlast its two inaugural partners due to good fortune and a loyal fanbase. As the NHL's first season dawned, the trials of the times and those fans and owners passions would make or break the Montreal Canadiens in the coming years.

The Senators, Wanderers, and Canadiens were three of seven teams present when the NHA formed in 1909 that were still viable when the NHL began in 1917. Montreal would outlast its two inaugural partners due to good fortune and a loyal fanbase. As the NHL's first season dawned, the trials of the times and those fans and owners passions would make or break the Montreal Canadiens in the coming years.The NHL's first season was a mere 6 games old when disaster struck and play was disrupted as a fire destroyed Montreal's stately Westmount Arena, home of the Canadiens and the Wanderers. Both clubs lost all their equipment. The Canadiens relocated to the Jubilee Rink, but Wanderers manager Art Ross folded his team because he thought the Jubilee was too far away from the Wanderers fan base.

Wanderers owner Sam Lichtenhein is best known for being unlucky with fires, which destroyed the arenas of two of his sports teams, one of his father's and one of his businesses. One of his father's department stores were destroyed in the 1871 Great Chicago Fire, after which the family moved to Montreal.

Wanderers owner Sam Lichtenhein is best known for being unlucky with fires, which destroyed the arenas of two of his sports teams, one of his father's and one of his businesses. One of his father's department stores were destroyed in the 1871 Great Chicago Fire, after which the family moved to Montreal. At the time of the fire, the Wanderers were drowning in problems, as they were hard hit financially because of the war. Owner Lichtenhein had threatened to withdraw from the league because of the scarcity of good players, due mostly to the outbreak of theWorld War I. Making matters worse the Cleghorn brothers, Odie and Sprague, were unable to play for the team. Sprague was still recovering from his broken leg while Odie couldn't play due to avoiding military enlistment. Things were so bad for the Wanderers, that the other teams sent some of their players to the Wanderers to keep them afloat. The Wanderers had a 1-5 record when the fire destroyed their Westmount Arena home.

The fire, which started in the Wanderers locker room, destroyed all the Wanderers equipment. The Montreal Canadiens who were also using the Westmount Arena that season returned to the Jubilee Rink with an offer to share the building with the Wanderers.

Another offer came from the city of Hamilton, however owner Sam Lichtenhein chose to fold citing he had already lost $30,000. Despite the suspicious nature of the fire there would be no official investigation for arson. Wanderers players would be distributed around the rest of the league.

The Canadiens fared much better in this sudden twist of fate. They called upon a previous offer by owners of the Jubilee Arena to return there without missing a game. Though the Canadiens had lost some equipement in the blaze, it is said that they were able to retain certain items - namely the players skates and some sweaters. Former Canadiens defenseman and goaltender Jos Cattarinich, who was still involved with the team, sold tickets for the Canadiens first rescheduled date at the Jubilee from his local business.

The Canadiens fared much better in this sudden twist of fate. They called upon a previous offer by owners of the Jubilee Arena to return there without missing a game. Though the Canadiens had lost some equipement in the blaze, it is said that they were able to retain certain items - namely the players skates and some sweaters. Former Canadiens defenseman and goaltender Jos Cattarinich, who was still involved with the team, sold tickets for the Canadiens first rescheduled date at the Jubilee from his local business.Here is an article from Collections Canada, recounting the Westmount Arena blaze:

Underwriters Inspectors Had Certified to Safety of Building Shortly Before the Outbreak Took Place

With the building just inspected and found to be in order by the inspectors of the Fire Underwriters Association, the Westmount Arena, home of hockey in Montreal for many years, and the scene of many historic ice battles and festivals, was totally destroyed by fire yesterday, the blaze starting shortly before midday. The flames, which originated between the floor of the secretary treasurer's office and the ceiling of the west side dressing room, spread so rapidly that it was impossible to save the building, the structure being burnt to the ground, causing a damage estimated by the president of the Montreal Arena Co., Mr. Ed. Sheppard, at $150,000. This is covered partly by an insurance of $50,000, an insufficient sum to rebuild the edifice in these times.

While no definite statement could be obtained last night as to the next steps of the company, it is believed the building will not be reconstructed, the probable cost being far in excess of the figures at which the house was originally built. The site, however, is very valuable and it is more than likely that the company's directors, when they meet this week, will decide to dispose of the property and close up affairs.

The loss of the building brought about the loss of several thousands of dollars in incidentals. Canadiens manager William Northey will lose a large Buick motor car which he had stored in the annex of the building for the winter, while the superintendent of the building, James McKeene, lost most of his household goods. The clubs which had the use of the rink for the winter will also be heavy losers, both the Wanderers and Canadiens, who were scheduled to play there last night, having lost all their uniforms, sticks, and other paraphernalia. The clubs of the Montreal City League, with the single exception of Loyola, which has just returned from Pittsburgh, also lost all their effects.

The cause of the fire could not be determined yesterday, though it is thought a defective electric wire was responsible. Underwriters had just inspected the buildings and they found that usual precautions had been taken by the company to prevent fire.

The explosion of one of the boilers used in the heating apparatus was at first thought to have caused the outbreak, but this was afterwards found to be erroneous.

On the ice, the National Hockey League officially had its beginnings on December 19, 1917, as the Montreal Canadiens defeated Ottawa 7–4 and the Montreal Wanderers downed Toronto 10–9. Those historic games, however, were preceded by more than a month of meetings and backroom dealings by a group of gentlemen that were entrusted with the formation of the National Hockey League (NHL) following the demise of the National Hockey Association (NHA).

On the ice, the National Hockey League officially had its beginnings on December 19, 1917, as the Montreal Canadiens defeated Ottawa 7–4 and the Montreal Wanderers downed Toronto 10–9. Those historic games, however, were preceded by more than a month of meetings and backroom dealings by a group of gentlemen that were entrusted with the formation of the National Hockey League (NHL) following the demise of the National Hockey Association (NHA).These meetings began in early November as the National Hockey Association’s directors, namely S.E. Lichtenhein of the Wanderers, George W. Kendall of the Canadiens, Thomas P. Gorman of Ottawa and M.J. Quinn of Quebec along with NHA secretary treasurer Frank Calder attempted to keep the league afloat. The numerous franchise problems in the preceding season, however, eventually led the NHA executives to start anew.

At the historic Board of Governors meeting in November 1917 at Montreal’s Windsor Hotel, the National Hockey League was formed. The crude 25 page constitution of the National Hockey Association, the NHL's predecessor, was adopted as the governing document of the new league. As president elect Calder told a sparse gathering of media, the purpose of the new league was the fostering and furtherance of the game of hockey to be governed by bylaws and rules.

The NHL's formation was a cunning affair. The NHA had admitted a military unit, the 228th Battalion, during the 1916-17 season, but it was called to active duty in February 1918. A majority of NHL owners were upset with Toronto owner Eddie Livingston for a variety of reasons. Livingston had owned the Toronto Ontarios, previously named the Tecumsehs and then later renamed the Shamrocks. He then purchased the rival Toronto Blueshirts and attempted to consolidate both Toronto teams in 1917. They also were tired of his constant demands regarding scheduling and player redistribution.

The NHL's formation was a cunning affair. The NHA had admitted a military unit, the 228th Battalion, during the 1916-17 season, but it was called to active duty in February 1918. A majority of NHL owners were upset with Toronto owner Eddie Livingston for a variety of reasons. Livingston had owned the Toronto Ontarios, previously named the Tecumsehs and then later renamed the Shamrocks. He then purchased the rival Toronto Blueshirts and attempted to consolidate both Toronto teams in 1917. They also were tired of his constant demands regarding scheduling and player redistribution.The other NHA owners used the 228th's departure to call for an even number of teams and dissolved the Blueshirts, promising to return Livingston's players later.

They didn't. Instead, they created a new four team league comprised of the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Quebec Bulldogs and Ottawa Senators.

The Bulldogs would fail to ice an NHL team for the 1917-18 season, temporarily reducing the league to four teams. Bulldogs owner M.J. Quinn was perceived in October of 1917 as being in with Livingstone's group in wanting to merge with interests south of the border in launching a rival league to the NHA. Quinn's financial concerns were later named as reasons for the Quebec franchise not being on board at the time of the NHL's creation. A club playing out of and under the control of the Toronto Arena company, under that name, was brought in by the league as a last minute replacement for the Bulldogs, who had to suspend activities for the season. Quebec players hence became free agents until the franchise was on solid ground once again.

The Bulldogs would fail to ice an NHL team for the 1917-18 season, temporarily reducing the league to four teams. Bulldogs owner M.J. Quinn was perceived in October of 1917 as being in with Livingstone's group in wanting to merge with interests south of the border in launching a rival league to the NHA. Quinn's financial concerns were later named as reasons for the Quebec franchise not being on board at the time of the NHL's creation. A club playing out of and under the control of the Toronto Arena company, under that name, was brought in by the league as a last minute replacement for the Bulldogs, who had to suspend activities for the season. Quebec players hence became free agents until the franchise was on solid ground once again.The morphing of the NHA into the NHL, with an exact league constitution, was ostensibly undertaken as a method for the league and owners to rid themselves of Livingstone.

"He was always arguing about something," said Ottawa Senators owner Tommy Gorman of Livingston. "Without him, we can get down to the business of making money."

In a delicious quote that is indicative of the freewheeling times, one owner was noted as saying that "we didn't throw Livingstone out because he still has his team in the NHA. The trouble is, he is playing in a one team league. We should thank Eddie. He solidified our new league, because we are all sick and tired of his constant wrangling."

Eddie Livingston did not take his exclusion lying down, suing players, teams, arenas and the NHL. A new Toronto NHL club, the St. Patricks, legally separate from the Toronto Arenas, was created in 1919-20, ending Livingston's quest to join the NHL. He tried to form a rival league, but was thwarted by moves taken by NHL President Frank Calder, beginning with the creation of the Pittsburgh Pirates franchise in 1925, and other American franchises that followed.

Both the Canadiens and Wanderers started playing in the Westmount Arena, which burned down after the Wanderers sixth game. That team was disbanded and its players were distributed around the league. Future Boston Bruins coach and general manager Art Ross played his only three NHL games for the Wanderers, scoring one goal.

Both the Canadiens and Wanderers started playing in the Westmount Arena, which burned down after the Wanderers sixth game. That team was disbanded and its players were distributed around the league. Future Boston Bruins coach and general manager Art Ross played his only three NHL games for the Wanderers, scoring one goal.The Wanderers were in trouble from the start of the season. They won their home opener but drew only 700 fans. The Wanderers then lost the next three games and owner Lichtenhein threatened to withdraw from the league unless he could get some players. Although they could have acquired Joe Malone in the draft they turned to the PCHA and signed goaltender Harry "Hap" Holmes. They also obtained permission to sign such players as Frank Foyston, Jack Walker and others if they could do so. The Wanderers loaned Holmes to the Seattle Metropolitans of the PCHA but he eventually found his way back to the NHL when Seattle loaned him to the Toronto Arenas.

A league meeting was planned to deal with the situation, however on January 2, 1918, the matter was resolved when the Westmount Arena burned down, leaving the Canadiens and Wanderers homeless. The Canadiens moved into the 3,250-seat Jubilee Arena. The Hamilton arena offered to provide a home for the Wanderers, but Lichtenhein disbanded the team on January 4, after the other clubs refused to give him any players. The remaining three teams would complete the season.

The Canadiens returned to the smaller Jubilee Arena where they had played their inaugural 1909-10 season, and the NHL was down to three teams.

The Canadiens 1917-18 lineup included, Georges Vezina, Newsy Lalonde, Didier Pitre, Billy Coutu, Bert Corbeau, Jack Laviolette, Louis Berlinquette and Evariste Payer. Joe Malone and Joe Hall were added from the dormant Bulldogs franchise while Billy Bell and Jack McDonald came from the Wanderers.

The Bulldogs loss would be the Canadiens gain in 1917-18, as Malone would establish a professional hockey record with his 44 goal season. The mark would stand as the goal scoring bar for 27 years until it was surpassed by Maurice "Rocket" Richard's 50 goal season in 1945. Malone averaged an incredible 2.2 goals per game - a standard no player would ever top.

The NHL's inaugural year would also see two other stars, the Senators Cy Denneny and the Canadiens Newsy Lalonde, curiously both Cornwall, Ontario natives, create equally impressive feats. Denneny's 36 goals in 20 games, and Lalonde's 23 markers in only 14 contests, set marks of 1.8 and 1.64 goals per game respectively.

Comparitively, Wayne Gretzky's 87 tallies in 74 games in the 1983-84 season, was good for a 1.18 goals per game average.

Though it couldn't be known at the time, Denneny and Lalonde also set upon owning the NHL's oldest record, that of an NHL player in his first season, not neccessarily a rookie by the definition of the times, scoring goals in their first six pro games. The feat was matched just once in 90 years of NHL history, by Evgeni Malkin of the Pittsburgh Penguins in the 2006-07 season - some 89 years later!

The Canadiens debut NHL season mirrored it's previous eight NHA campaigns in that it was filled with change, unpredictability, and certain constants.

For a third consecutive season, they would battle for the league championship with an eye on reaching the Stanley Cup finals. Despite the setback and demoralizing aspects of their home arena burning to the ground, Montreal would write a very interesting chapter to their NHL beginnings.

For a third successive season, Lalonde would act as player and coach for the team, while George "Kennedy" Kendall would remain it's manager.

A line was formed with Lalonde at center, Malone converted to left wing, and Didier Pitre on the right. The three stars would account for 84 of the Canadiens 115 goals during the 22 game season.

Malone, a native of Sillery, Quebec who donned the Bulldogs colours for nine seasons, would have a career year in his first season in Montreal. Not only did he raise the goal scoring standard, he set a points total mark of 48, notched seven hat tricks, scored 5 goals on three different occassions, set a one game mark for most total points with 6, and had a 14 goal goal scoring streak during the season.

The record of 7 hat tricks would not be bested until Mike Bossy of the New York Islanders topped the mark in 1980-81 with nine.

Malone would play part of the following season with Montreal before being returned to the Bulldogs for the 1919-20 season. After two season with the Hamilton Tigers, he would return to Montreal for two more less productive campaigns. In his NHL 7 year career alone, Malone would post 146-18-164 totals in 125 games.

George Vezina would record the NHL's first shutout - a 9-0 blanking of the Ottawa Senators. He would lead the league in wins with 13 and GAA with a 3.93 average.

Four days prior to the season's start, the Canadiens and Wanderers would play a benefit game for homeless victims of an explosion in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The Canadiens Joe Hall, a longtime Newsy Lalonde rival, was suspended by the league and charged with assault by Toronto police after a stick swinging incident with the Arenas Alf Skinner on January 28.

In the NHL's opening game of the 1917-18 season, Ottawa defenseman Dave Ritchie, scored the first goal in NHL history, before scoring a second in the victory over the Wanderers.

Ritchie probably wasn't surprised to find that Joe Malone was the league's opening night leading scorer, with five goals, after his Canadiens downed the Senators. After all, Malone had been the leading scorer for the NHL's predecessor, the NHA, for the second time the previous season. Malone, who would score seven goals in a 1920 NHL game, led the League in its first season with 44 goals in 20 games, a scoring pace never equaled in NHL history.

The first NHL season was a 22 game affair, split in "halves," with the first half winner to meet the second half winner for the right to challenge the Pacific Coast Hockey Association champion for the Stanley Cup.

The first NHL season was a 22 game affair, split in "halves," with the first half winner to meet the second half winner for the right to challenge the Pacific Coast Hockey Association champion for the Stanley Cup.Malone and goalie Georges Vezina led the Canadiens to a 10-4 record to win the first half of the season. Toronto won the second half with a 5-3 mark, and then won the two game series with a 10-7 edge in total goals.

Combining the two half seasons, Toronto and the Canadiens both finished 13-9, while Ottawa was 9-13. The Wanderers were 1-5 at the time of the Westmount arena perishing.

Toronto went on to beat the Vancouver Millionaires in a five game series to win the Stanley Cup. Reg Noble, who briefly appeared as a Montreal Canadiens player in 1916-17 and was later an NHL referee, led Toronto with 30 goals. Noble would become the last active player from the NHA to perform in the NHL. He retired following the 1933 Stanley Cup playoffs. Harry "Hap" Holmes was the goaltender, although Arthur Brooks played four games and Sammy Herbert one.

It wasn't until later that NHL officials officially called the Toronto team the "Toronto Arenas." The name wasn't engraved onto the Stanley Cup until 1947, long after the tradition had begun. The NHL didn't control the Stanley Cup in 1918, but it would in 1947.

A note on photos included in this post: None of the pictures of the Montreal Canadiens are from the 1917-18 NHL season. There were quite simply none to be found.

.